Monday; so glad to be back to school. It is, after all, the reason we’ve come, and it seems so meet so sporadically. Now all classes are shortened to ½ hour to allow time in the school day to practice folk dance for the August 15 independence day celebration. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independence_Day_(India)

We had orientations, and days off, and shortened classes and everything BUT school. I feel a bit claustrophobic and homesick at the hotel, but never at school. The teachers are warming up a bit and opening up a bit, but the children are—much like the students at home–a breath of fresh air. They just make you smile. Back home, there have been many occasions when I have come to school angry or depressed or in a foul mood for one reason or another, and the kids invariably make me smile. It’s one reason to be a teacher. It keeps you, by necessity, an optimist.

The kids here are just absolutely wonderful. The depth and power of cultural mores is stunning. At home, most kids are great—even the attention hogs and the stinkers are likeable once you get to really know them. There is, on occasion, a student with profound problems, but after13 years of teaching high school I can count on one hand the number of kids who have failed to charm me. While that is true, it is also true that in American culture, you need to get to know the kids. It takes a bit of time for them to trust you, to warm up to you. To some degree, you have to earn their respect. I find that all it takes is a seriousness of purpose, fairness, and a genuine interest in hearing what they have to say. I think it’s a fair enough pact.

The kids here, on the other hand, demonstrate—so far to a person—a respect for authority (a smile and a good morning, m’am every single time!) and an implicit respect for education. I am stunned. I keep looking for that one child who can’t or won’t meet my eye, who is suspicious of the stranger, who needs to warm up. I have yet to find her.

In conversation with teachers in the staff room, though, they agree with my analysis of children—they say Indian children are the same; they also need to get to know you; you also have to earn their respect. I guess the layer of politesse is just more prominent in this culture than in ours.

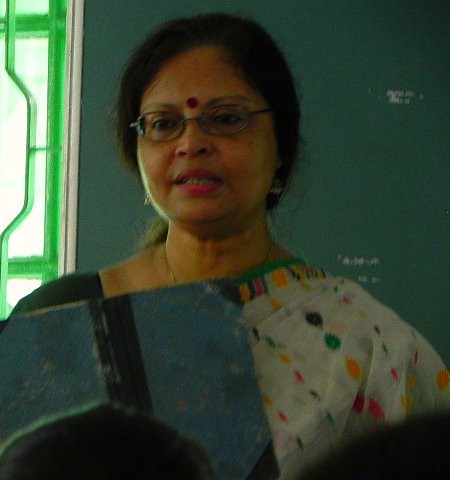

Monday I teach only two classes. Subha lets me observe her first class in the morning (the first class I’ve been permitted to observe here.) It is just as I had imagined. Lovely and charming Subha has a grace and ease with the girls—clearly a great deal of affection flows between them.

And they engage earnestly and sincerely with her as she works though a text with them. In spite of the large numbers and the short period, the class is interactive and productive.

Then I meet Julie Roy’s 8th grade class for the first time. This week, our introductions have a bit more structure. I ask them to write “auto-bio poems” (Thank you Carolyne White!) They go like this:

[your first name]

[four descriptive traits]

Sibling of

Lover of

Who feels

Who needs

Who gives

Who fears

Who would like to see

Resident of

[last name]

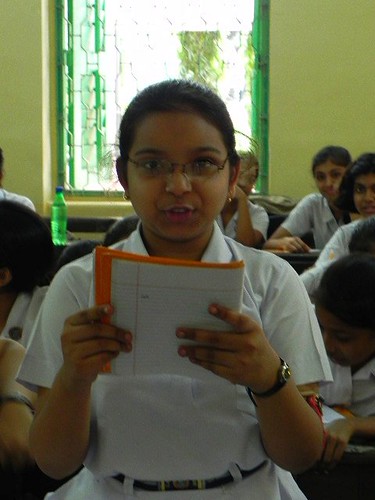

The kids are more creative and follow instructions much more easily than kids at home typically do. And their poems are touching. Descriptive traits include loving, honest, caring, and usually a nod to naughty. They want to see everything from the Northern Lights to Robert Pattinson to the United States. Some want to see peace in the world, some a greener planet, others want to see their parents happy. There are fears of reptiles, snakes, their parents, an uncle and terrorists. There are many declarations of love for the city and the country, and many declarations of gratitude for being alive in this beautiful world. They would, as Frank McCamley would say, “cheer the heart of a wheelbarrow.” (Did I quote that accurately, Frank?)

And Subha’s first-language 10th graders are wonderful, too. We write and share auto-bio poems, and they are focused during the writing portion and open, creative, and sweet during the sharing portion. The only time I have to correct them is when there is talking when someone is sharing. But the room is huge, the class is large, and some of these children speak barely above a whisper. Correction: some of them clearly whisper. I have to put my ear close to their mouths to hear them. When I ask the others to be respectful and listen they do, even though in many cases they clearly cannot hear a thing.

By Tuesday morning, I have finally met all of the classes I will teach except one (14 of them!). The 12th grade class I teach last is a class of 90!!! (A few are absent.) The teacher stays in the room (some teachers stay, some leave, some ask my preference, some ask permission to stay) and provides a microphone that works only sporadically. I have every girl read her first name and her most creative or significant line from her poem. Everyone has an opportunity to speak (although I can hear and/or understand maybe 1/3 of them). It’s a large-scale, group auto-bio performance! School is over early for independence day-dance practice. Ashu and I watch them practice today:

I don’t see as much as I’d like, though, because as they practice, groups of girls keep coming up to me to talk. They want to know all about me; they want me to know their names. They want me to remember their names. They give themselves simple nicknames so that I can remember them. I tell them that I need a list. Seeing the names will help (might help?) me to retain them.

Wednesday: MONSOON! It is our first significant rainfall (it has rained briefly nearly every day.) and the ground quickly turns in to pools. Teachers and students carry umbrellas; the hall outside the staff room is colorful with drying umbrellas. I have to be careful not to slip on some of the floors that have the potential to be very slippery when wet.

Monsoon pictures from Aysha (see Team India group on facebook):

It is one week since I have arrived at the school. I still need help navigating the various buildings, nooks and crannies. I haven’t been to the same class twice yet. I have one last group to meet (I didn’t get to the first class last Wednesday.) It is a 6th grade class, and I greet them and apologize for brief introductions (I do take a few questions—more of what’s my favorite color, what movie actress do I like, how do I like Kolkata….). Some of the girls have prepared a song about the rain to welcome me:

We then read through Langston Hughes’ poem, A Dream Deferred. I ask them if they know about race relations the U.S. They look blank. I ask them if they know that in the United States Black people used to be kept as slaves. Oh yes, they nod vigorously. Did you learn about our Civil war—yes, yes, and Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves—yes. They know the Emancipation Proclamation. (How much would any American student know anything about Indian history? I suppose some would know about the caste system.) Well, I tell them, there was lot of work to be done even after the slaves were freed. White people were still very prejudiced against black people and there were separate schools, water fountains, restaurants—much like the untouchables in your caste system. They nod vigorously. We have a brief discussion of the anger embedded in the poem. They copy it into their notebooks. We will follow up on it in a subsequent class.

When I have a similar discussion with a group of older students, they are very, very interested in the congruencies between our system and theirs. But when I suggest that they, with positive economic growth and their efforts toward democracy, are perhaps on a positive trajectory while we have hit some roadblocks—our debt, our Democrat/Republican impasse, our de-funding of education and health care programs, they don’t buy it, telling me that it is very clear that their government is corrupt.

They want to know how I like Kolkata. When I say that I love it—that it is a beautiful, lush city brimming with people, vibrant with color, they look askance. What about how dirty it is, what about all of the beggars, the crowds? They have a point. Well, I told them, I suppose that as a guest I’m looking at the city through rose-colored glasses, but you just have so many, many more people than we do. It’s really a total immersion into humanity—rich and poor, educated and uneducated, Indian and non-Indian—it just pulses with life. They don’t buy it. What do you think of the dogs, they ask; of the traffic (okay, they have me on that one) of the pollution?

We’ve been anticipating the cancellation of school on Thursday all week. There is to be a political rally at the local stadium. The democratically-elected left-wing communistic government that had been in power was unseated in May, and the newly elected party is holding a rally tomorrow. It will be in the stadium right near our hotel and they are anticipating an influx of people from outside of the city, and gridlock. The school decides to open just for the morning (perhaps so the teachers do not have yet another make-up day) but Ashu and I are told not to come. It might be too difficult for us to get back to the hotel though the gridlock. I am so disappointed—another day in and around the hotel—so much to see and do, so many kids to talk to, so many classes to teach, and it continues to come in dribs and drabs. Ah well, perhaps I can catch up on my blog.

From The Times of India:

Meanwhile, braving the rains, thousands of Trinamool Congress workers and supporters were arriving in processions at the Brigade Parade ground here for the party’s annual Martyrs’ Day rally which would also mark the party coming to power in the state with a massive mandate ending over three decades of Left rule in West Bengal.

In other news, Subha has been reading Kristof & WuDunn’s book, Half the Sky, and asks if I remember reading about Urmi Basu who runs a shelter for trafficked women in Kolkata. I do—and she tells me that she knows her. In fact, we can go to visit her shelter, New Light, on Friday. There are no classes (!) as it is the run-offs for the big quiz tournament on Saturday. There will be 30 schools here competing for six slots, the final six compete on Saturday (Frank—I wish you could have seen their quiz teacher (yes!) in action), but neither Subha nor I have duties on Friday during the semi-finals, so she has gotten permission to leave with me (and Ashu, and anyone else in our group who wishes may accompany is) and we will visit Urmi’s shelter. She also knows a local environmentalist who worked very closely with Mother Teresa, has written one book on her and is writing another, who is willing to give us a tour of her various sites. This will make the day off on Thursday a bit easier to take.

Thursday is another monsoon. There is a significant leak in my room so I have to move to a new room—a pain; one settles in quite a bit in two weeks…. I sleep until 8 (guess I’m past the jet lag) and eat with several other teachers. We watch the heavy rains as we eat a late brunch. Several of us go to the bar/lounge area to blog, write, engage in various computer-related work, then some of us gather in Bree’s room to watch a DVD of the work that Sister M. Cyril Mooney has been doing at Loreto Sealdah Day School. I wonder that she has not received the Nobel Peace Prize yet. The programs and initiatives at that school are extensive and the most radical I have ever heard of. Fifty percent of the children are middle class/privileged, 50% are from the poorest in the city. Sister worries that the poor will adopt the value system of the affluent and talks about the “cycle of affluence.” She wants the affluent to learn to empathize with the poor, to stay here in India to make change. The doors of her school are always open, anyone is welcome. She has programs for the rural villages, for children working in the brickyards. Two hundred fifty homeless children sleep in the school building at night (they were homeless; the building stood empty after school hours…why not?) Be sure to read about it online, and I will report back as I see more of this exceptional program.

Tomorrow off to meet Urmi Basu!